The initial visual impression one gets of Bunga is of striking coastal beauty: partially forested undulating hills running down to the ocean. There’s some remnant farmland suggestive of its European agricultural past, but mostly the vista is of eucalyptus woodland, pockets of rain forest in the valleys and a ribbon of coastal heath along the shoreline. There are very few visible dwellings.

With this second post, I’m looking to get a basic understanding of the geology of Bunga, thinking that in order to understand how various types of flora and fauna have interacted in this area over time, I need to learn about the soil and to do that, I need to learn about the underlying geology.

Bunga’s geology turns out to be way more interesting than I could ever have guessed. Indeed, while (as we saw in my first post) Bunga itself is almost unknown, its underlying rock formations have received quite a bit of attention from archeologists and ‘deep time’ geologists.

But to start with a simple description, like most of the east coast of Australia, the geology of Bunga is a mix of sedimentary rock laid down over time with some igneous rock either intruded from below or erupted volcanically. If one walks along the beach front, one quickly gets a sense of how heavily folded and faulted the underlying geology of the area is. Some of the most interesting geological action at Bunga took place way back in the Devonian Period. (For any newcomers to geological time like me, the Devonian Period spans between about 419.2 million and 358.9 million years ago. This is a very long time ago and is sometimes known as the Age of Fishes — so, way before dinosaurs and nearly all land-based fauna. Australia was still joined with South America, Africa, India and Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere super continent of Gondwana.)

The sedimentary rocks that dominate Bunga’s geological profile today have been traced back to the Middle to Late Devonian Period, when much or all of the area was underwater (either lake or ocean). Underwater layers of conglomerate rocks, shales, sandstone and some ‘reworked volcanics’ were deposited and accumulated over time (Lewis et al 1993: 9-12, 92-3). Archeologists and paleogeologists have been sufficiently interested in the area because of its fossil record, that they have named the main sedimentary area the “Bunga Beds”.

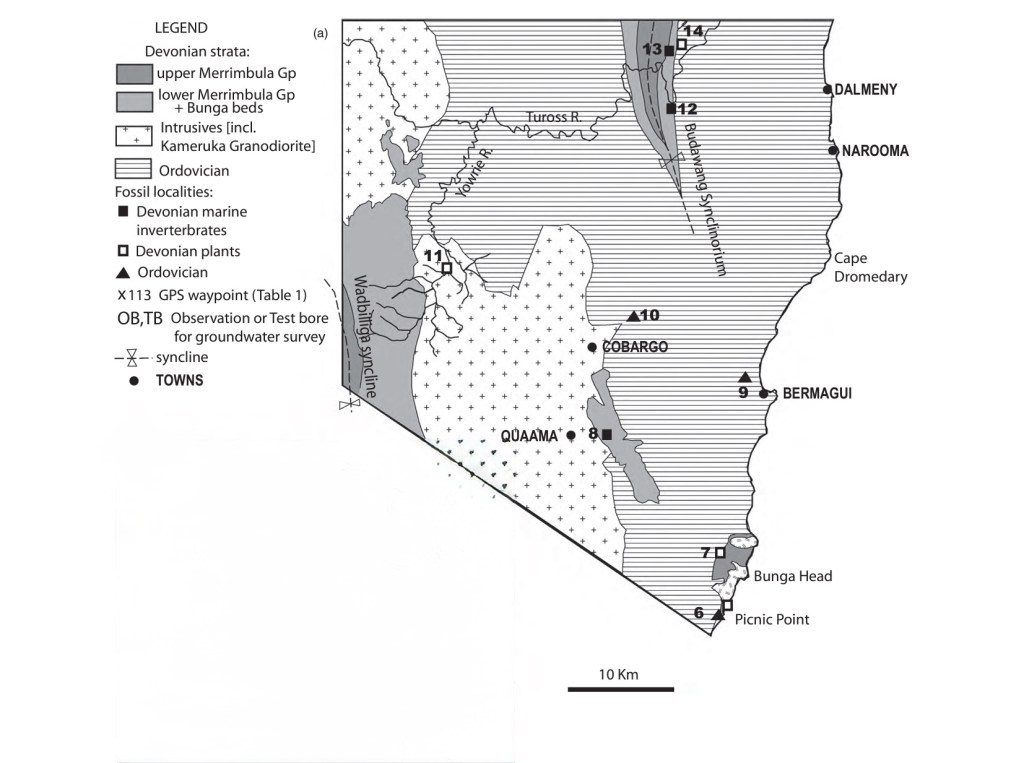

Geological and Archaeological Profile (Dunstone & Young 2019: 63)

Recent geological research suggests the Bunga Beds were laid down in the Middle Devonian Period, with the main volcanic material following in the Late Devonian. The most visible volcanic rocks are the dramatic ocean cliffs of Bunga Head, which abut the southern edge of the Bunga Beds. Bunga Head turns out also to be the northern outlier of the Boyd Volcanic Complex centred further south near the town of Eden.

Bunga Head, taken from Hidden Valley Beach

The other striking element of Bunga’s geological profile is the outcrop of the igneous rock, gabbro, north of the Bunga Beds at Goalen Head. Gabbro turns out to be uncommon in this part of Australia, and the large dark boulders at Goalen Head are quite picturesque.

Goalen Head (photo courtesy of Mark Spittle)

Gabro boulders at Goalen Head (photo courtesy of Mark Spittle)

Plant and fish fossils found in the Bunga Beds contain remnants of early freshwater sharks (Acanthodii) and tree-like mosses (Arborescent lycopsids) that are thought to be evidence of some the earliest forest environments on the Gondwana super-continent (Young 2011: 995). It’s fascinating to think that this small and obscure place, Bunga, gives us a valuable window into the deep past of plant and animal life.

This is the beginning of my learning about the geology of Bunga, but already I can sense how so much of natural history is shaped by our geology. And further, how it provides a record of big changes in flora and fauna over extremely long periods of time. If you are able to correct anything I have written here, or have questions or thoughts, please just type them in the comments section below. I’ll explore the soil coverage of Bunga in a later post; for now I find myself full of new wonder about the secrets to be learned from ‘what lies beneath’.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Brett Evans, Eleanor Nebel, Oliver Nebel and Mark Spittle for helpful discussions in exploring this subject.

References

R. A. F. Case et al. (2001) Sedimention and re-sedimentation of pyroclastic debris in lakes, Spec. Publs Int. Ass. Sediment, 30, 83-108.

R. L. Dunstone & G. C. Young (2019) New Devonian plant fossil occurrences on the New South Wales South Coast: geological implications, Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 66:1, 57-7.

P. C. Lewis et al. (1994) Explanatory Notes Bega—Mallacoota 1:250,000 Geological Sheet SJ/55-4, SJ55-8, Geological Survey of NSW, New South Wales Department of Mineral Resources, pp. 168.

NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service (2011) Mimosa Rocks National Park: Plan of Management, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water, pp. 86.

G. C. Young (2011) Devonian formations, vertebrate faunas and age control on the far south coast of New South Wales and adjacent Victoria, Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 54:7, 991-1008

Leave a reply to Erica Tippett Cancel reply