I’m still casting around trying to get a solid grip on what might be thought of as the ‘framing factors’ of the natural history of Bunga. My aim is to understand the variety of plant and animal species that exist here and how they have interacted over time, but so far I haven’t got beyond two factors: the underlying geology and the coming of Homo sapiens of various sorts.

In my last post I was looking at the devastating impact of the arrival European people for the first human settlers. White settlement wasn’t just devastating for Aboriginal people, it was also devastating for trees. In the state of NSW alone, by 1890 it is estimated that 9.9 million hectares of forest had had been destroyed as European settlers oversaw the ringbarking of trees to clear the land for livestock (Guppy 2024: 58).

On our own property, and others nearby in the Bunga area, there are plenty of reminders of this — from the sections of land completely cleared of trees for cattle in the late 1800s, to the scarred ‘skeletons’ of once large Eucalyptus trees that were felled or mutilated by settlers struggling to make a living off the land for themselves. But as against this, tree destruction and tree removal campaign by humans coming from Europe, there has been a seemingly irresistible tendency for trees to regrow and recover the land, unless prevented by some other factor.

Europeans settling on the land in Bunga struggled to get by. Various landowners tried to make a living with dairy and beef cattle, including Mark and Sarah Jones and some of their descendants. It seems that unlike other areas, the soil quality was simply not good enough and by the second half of the twentieth century land ownership passed to people whose living was no longer dependent on the land itself.

While the soil may not be rich enough to permit full time primary production, it clearly does allow some plants to flourish, ranging from towering Eucalyptus bosistoana (coastal grey box) and Eucalyptus longifolia (woollybutt) to lush rain forest trees such as Doryphora sassafras (sassafras), Syzygium smithii (lilly pilly) or Ehretia acuminata (Koda). I’m seeking to understand what the soil conditions are that permit this.

When discussing southeast NSW in their pioneering study of geology and landscapes, Costermans and VandenBerg (2022: 521) note the existence of a “coastal zone” running north-south, up to a few kilometres wide and rising to not more than 80 metres above sea level. Their characterisation of it as being “made up of estuaries, lagoons and old coastal sand barriers, as well as the broad valleys and the rocky cliffs and buffs” perfectly describes the topography of the Bunga area.

An earlier post looked at the geological foundations of the Bunga area, and noted that it was predominantly layers of sedimentary rock (mudstone, shales and the like), with a small patch of volcanic rock extruded from beneath (giving us the dramatic Bunga Head cliffs) and an area of igneous Gabbro (readily visible in the striking dark boulders at Goalen Head). Today’s topsoil was formed from the weathering over time of these underlying rocks and their mixing with decaying organic matter.

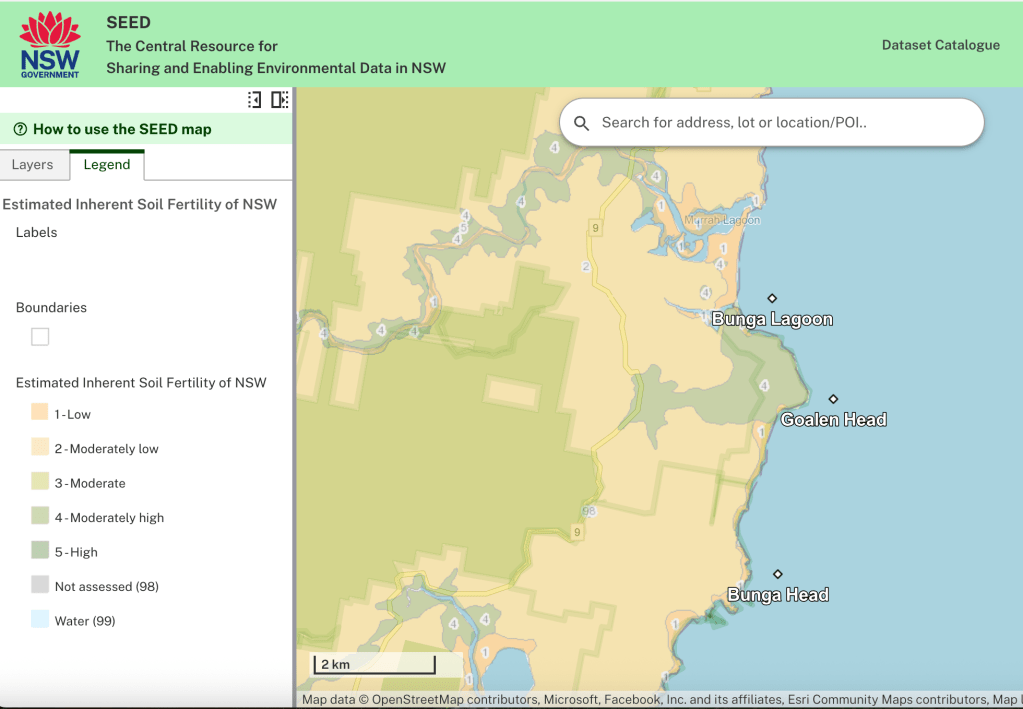

Roughly speaking, the underlying geology determines the parent rock from which topsoil is derived, and this is a major determinant of what the land will allow to grow. Some sense of this can be gleaned from the map below showing the estimated inherent soil fertility in the Bunga area. Without going into detail, with the exception of the moderately high fertility soil at Goalen Head (the so-called “chocolate soil” deriving from the Gabbro rock) and the alluvial soil along the river banks, the soil in the rest of Bunga is classified as only moderate-to-low fertility.

Not surprisingly, the more fertile soils support pasture where modest small-scale cattle farming survives, and the poorer soils are mostly covered with trees of various types. Important though, soil quality isn’t the only factor determining what the land will allow to grow.

A sense of this is immediately apparent from the second map overlay of the Bunga area (below) specifying the location of different categories of native vegetation. Again, without going into the details, the range and distribution of colours indicate much greater diversity of vegetation types than the soil fertiliy map would seem to suggest. For instance, on our property (between Goalen Head and Bunga Head) the soil is uniformly classified as moderately low fertility. And yet within fifty metres, as one moves steeply down into valleys the vegetation can shift from scattered large Eucalyptus to dense and lush coastal rainforest.

Clearly other factors — not just soil type — also have a bearing on what grows where. Moisture levels and exposure to sun and wind also matter. I need to develop some way of taking account of all these factors (and maybe others as well) to get a more satisfactory way of understanding why the plants the land allows to survive can vary so significantly within short distances.

References

Costermans, L. & F. VandenBerg. 2022. Stories Beneath Our Feet: Exploring the Geology and Landscapes of Victoria and Surrounds, Costermans Publishing, Frankston, VIC.

Guppy, M. & S. 2024. Ballara: A Natural History, Ballara Press, NSW.

NSW Government. SEED (Sharing and Enabling Environmental Data in NSW), link

Leave a comment