There have never been many people living at Bunga; the soil is not good enough. In the previous post, we saw a little of how the first humans came to and spread through the land mass we now call Australia and the sorts of environmental factors that governed early patterns of human settlement. Here at Bunga, places such as Hidden Valley Beach and Bunga Lagoon had provided attractive campsites for the Djiringanj people as well as Aboriginal people from other regions over thousands of years before the coming of Europeans.

The arrival of British colonizers, seeking — like all colonizers — economic advantage for themselves, had rapid and profound consequences for the original human settlers. Here on the far southeast coast, it began in the 1790s with itinerant gangs of sealers and whalers coming down from the fledgling colonial settlement of Sydney. They were followed in the 1820s and 1830s by squatters who came overland with cattle and sheep and settled, unilaterally claiming huge tracts of land for themselves.

After having lived in geographic isolation from the rest of the human species for tens of thousands of years, the arrival of British colonisers had devastating consequences for Aboriginal people. They had no immunity to the transmissible diseases the Europeans brought, and little defence against highly lethal European military technologies. In his celebrated ‘history of place’ about the far south coast, Mark McKenna (2022: 44-5) reports current estimates of perhaps 4,000-5,000 Aboriginal people living in the region in the late 1700s (before the coming of Europeans), but that this figure had fallen to less than 700 by 1850, and to less than 100 by the 1890s.

As one mid-19th century senior colonial official put it: “We hold (the land) neither by inheritance, by purchase, nor by conquest, but by a sort of gradual eviction. As our flocks and herds and population increase…the natural owners of the soils are thrust back without treaty, bargain or apology …depasturing licences are procured from government, stations are built, the natives and the game on which they feed are driven back…the graces of their fathers…trodden underfoot (quoted in McKenna 2002:280

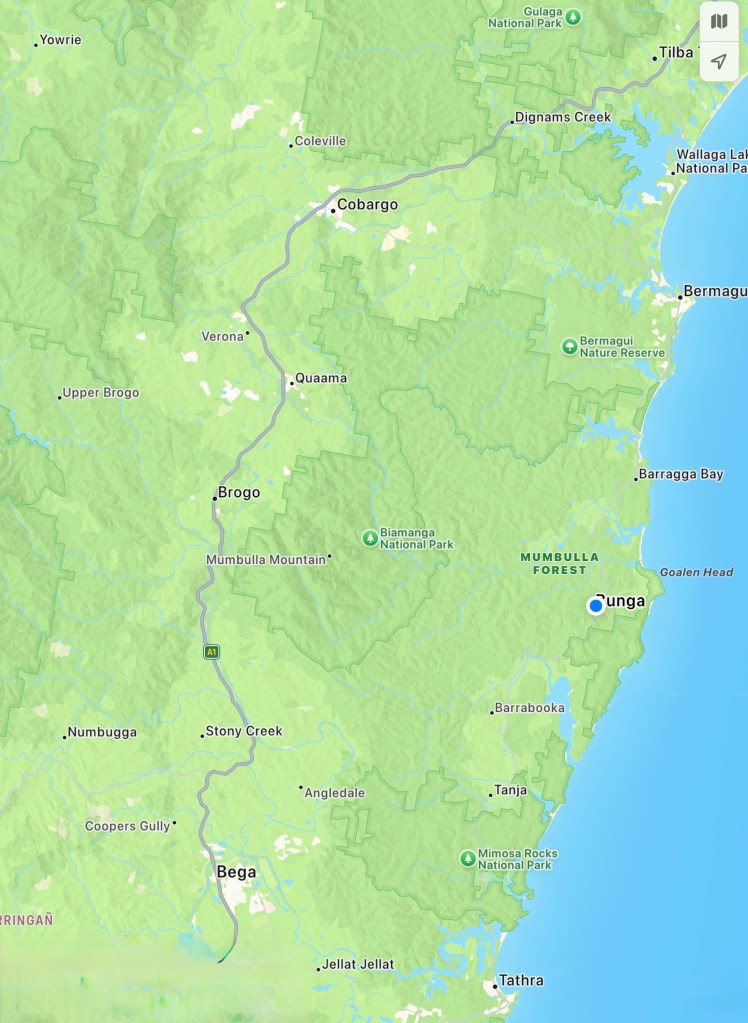

It was along ancient bush paths created by Aboriginal people that British settlers, their livestock and convict labourers walked as they ventured south from Sydney, establishing new inland towns such as Cobargo (43km northwest of Bunga) and Bega (36km southwest of Bunga) in the 1820s. And these inland towns soon begot beach landings and coastal settlements such as Bermagui (18km north of Bunga) and Tathra (26km south of Bunga) facilitating the much more rapid transport of rural produce by sea to metropolitan markets.

The spread of settlers to areas Bermagui and Tathra — like Bunga — took longer. One of the first was the fearsome figure of George Nelson, whose name is now attached to a beach, lake and creek. A large man, known for always carrying a brace of pistols, he constructed a hut in 1846 at Tanja, just a little south of Bunga. Nelson was described in the Bega Gazette of 19 December 1872 as a shadowy figure, who hunted Aboriginals with his dogs and may have been murdered in mysterious circumstances.

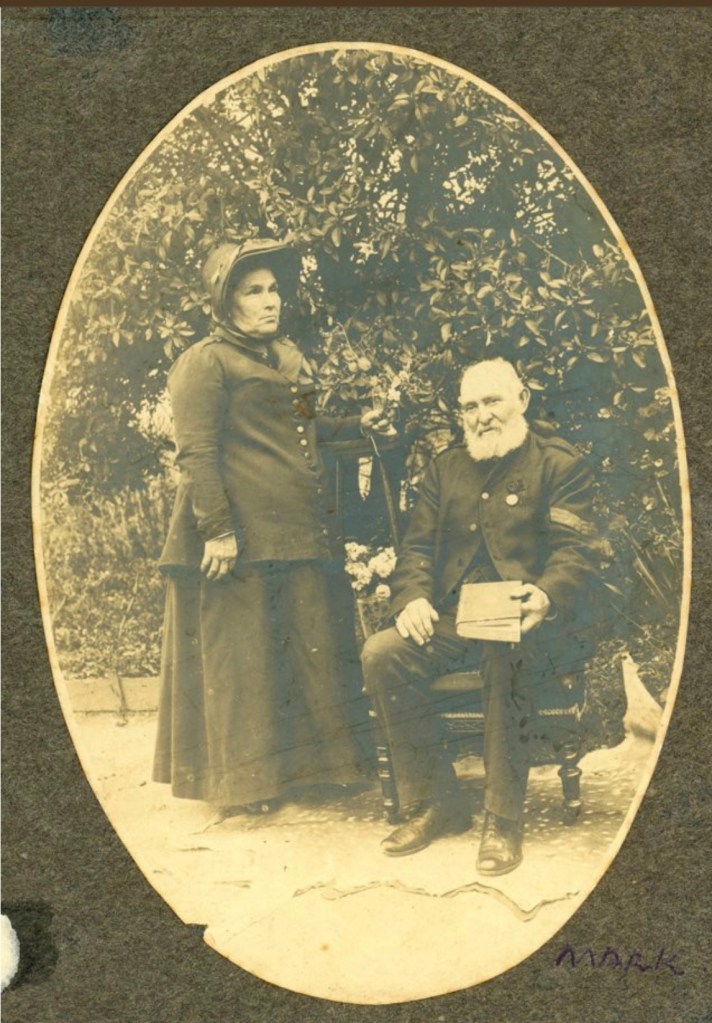

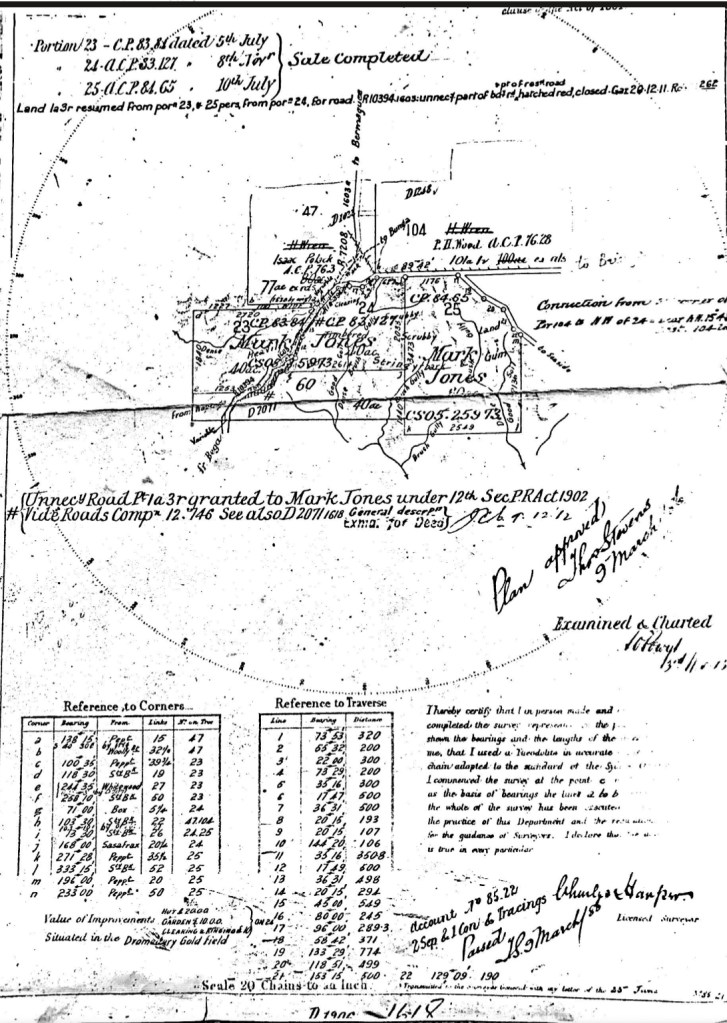

An important accelerant of wider European settlement was the Robertson Land Act of 1861 which resulted in the break-up of the early squatting land empires and paved the way for growing numbers of small land owners. Under the Act, a parcel of land could be be purchased from the colonial government with a small deposit for the modest price £1 per acre. Mark Jones was among the very first to purchase land in Bunga. Having arrived from England as a free settler in 1859 and then working for a time as a farm labourer south of Sydney near Milton, Jones purchased a total of 220 acres of virgin bushland at Bunga in the early 1880s.

Together with his wife Sarah, Jones constructed a “primitive house and outhouses out of string bark poles, slabs and bark” (Jones 1989:8). Life was hard. Mark, Sarah and their children had to clear the land by hand, struggle to grow vegetables and protect them with hand-cut wooden fences, and when enough land was cleared and pasture developed, establish a small dairy. The cream from the cows was churned for butter that was salted, packed and shipped to Sydney from Bermagui.

The land at Bunga my wife and I delight in living on today is the same land Mark and Sarah Jones lived on until their deaths over a hundred years ago. It is the land Mark purchased from the NSW colonial government. And it is the same land that was once enjoyed by the Djiringanj people, as they moved through this country with the shifting of the seasons.

References

Jones, Ray. 1989. “Growing up in Bermagui”, in Steve Elias, (ed), Tales of the Far South Coast vol 4, Bega.

McKenna, Mark. 2002. Looking for Blackfella’s Point: An Australian History of Place, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney.

Russell, R.M. 1978. 1846-1978, A History of Tanja: Compiled to Commemorate the Centenary of Tanja Public School, Tanja.

“Three Brothers, Or, Some Incidents in the History of the Bega District”, Bega Gazette, 19 December 1872.

Leave a comment