My previous post was an initial investigation of the basic geology of Bunga and how it has changed over time. There’s a whole lot more to be uncovered on that front, but this month I want to open another big topic: the evolving interaction of animal species at Bunga, starting with what may be the most consequential of all species — Homo sapiens.

Today, there aren’t many humans living at Bunga: perhaps, between fifty and one hundred of us. My impression is that nearly all current regular human residents are of European or Asian descent. But 150 years ago the only people living regularly at Bunga were the Djiringanj people of the Yuin nation, direct descendants of the very first Australians.

Thanks to the work of prehistorians and their advancing research techniques, we now have a much clearer picture of the peopling of Australia, and from that can make some inferences about the peopling of Bunga.

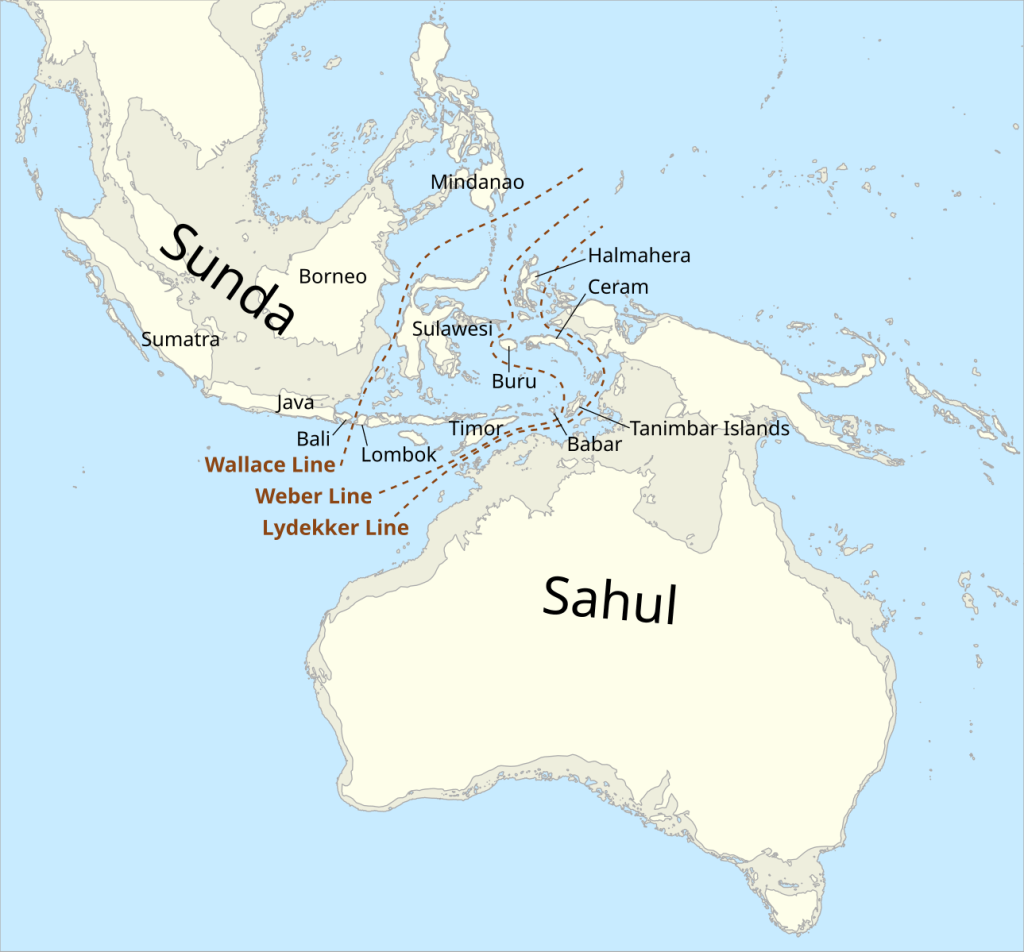

We now know with confidence that the first human colonisers of what we today call Australia came by sea 50-60 thousand years ago from the then Southeast Asia land continent of Sunda. Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania were at that stage all still joined as a continent prehistorians call Sahul. (Both Sunda and Sahul had been part of the more ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, mentioned last time.)

Source: Wikipedia

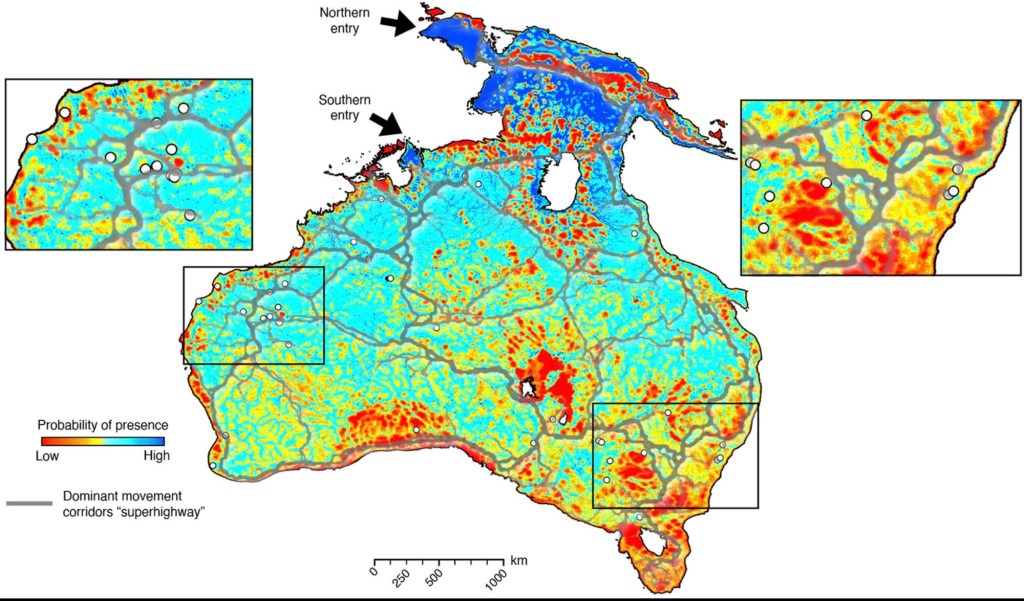

Debate continues about the specific routes by which humans spread around Australia, but it seems environmental conditions of the time had a major bearing on the routes by which human dispersal took place. Recent research (Salles et al. 2024) models how changes in the landform at the time shapes the probability of human pathways and settlement across the continent.

White circles indicate locations of archaeological sites.

Source: Salles et al. 2024:8.

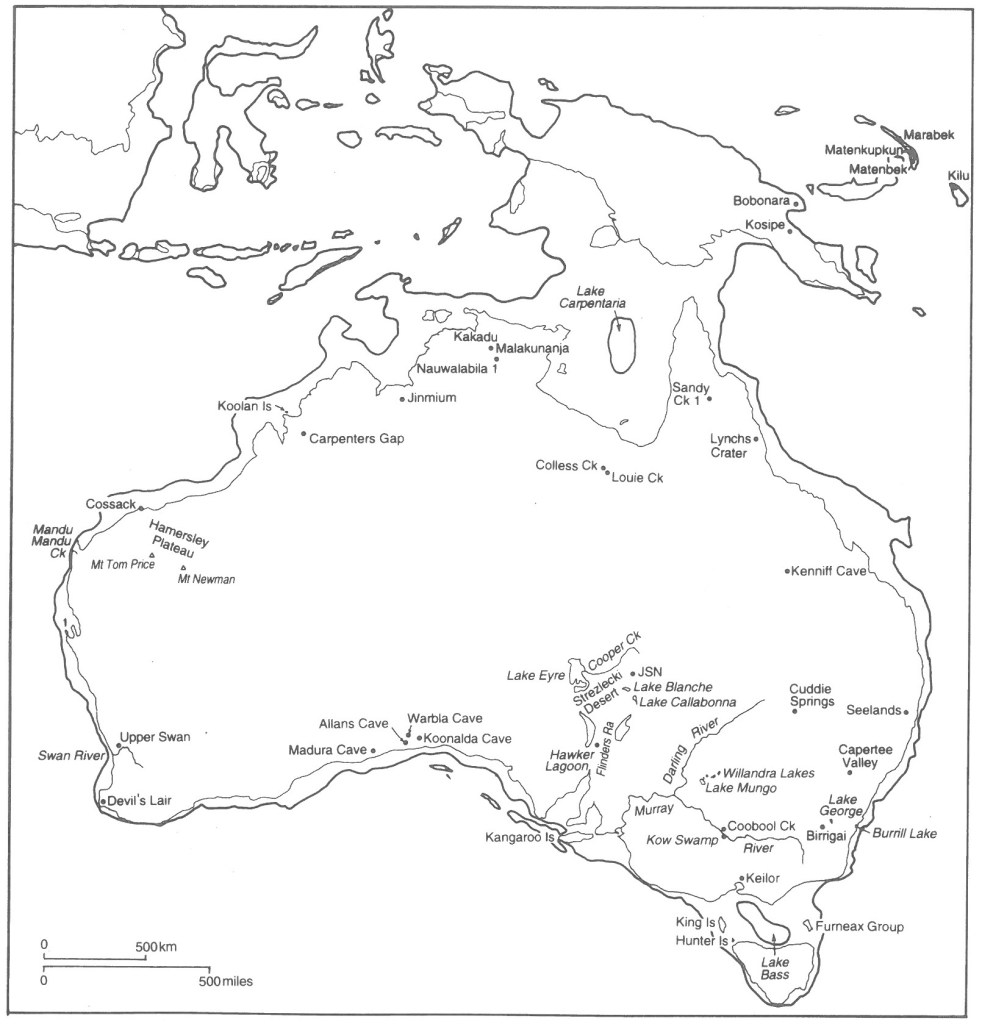

One of the primary texts of Australian prehistory reports that most of Australia had been explored and occupied well before 30,000 years ago (Mulvaney & Kaminga 1999: 132). In terms of the far southeast coast, the earliest archaeological record of human settlement is a rock shelter at Burril Lake (170km further up the coast from Bunga) which dates back to about 20,000 years ago. Much of the archaeological record that far back is now underwater and lost to us due to sea level rises as global temperatures increased following the end of Earth’s last cold phase about 12,000-15,000 years ago. Around 6,000 years ago, the sea level stabilised, giving us the coastline we know today. From that time, and especially over the last two to three thousand years, there was an intensification of human settlement along the southeast coast (Mulvaney & Kaminga 1999: 103, 130, 175, 274).

Source: Mulvaney & Kamminga, 1999: 157

In terms of lifestyles and settlement patterns on the southeast coast, archaeological evidence (Lampert & Hughes 1974) together with oral histories handed down among First Nations people (Cruse et al, 2005) indicate the region came to support a sizable population, with people accessing a wide range of shellfish such as mussels, oysters and abalone, as well as plant-based foods, medicines and other useful material from the coastal rainforests. Regular campsites on the coast seem typically to have been located close to freshwater estuaries and lagoons, rock shelves for easy access to shellfish, and shelter from the weather.

If we focus in just on our small locality of Bunga, places such as Hidden Valley Beach and Bunga Lagoon would have been prime candidates for Djiringanj campsites — both before and after the arrival of Europeans.

Source: National Parks NSW

Just as Captain Cook recorded seeing the smoke of campfires as he sailed up the coast in 1770 prior to coming ashore at Botany Bay, so it seems likely some Djiringanj people would have seen both Cook’s ship and those of the first English settler fleet in 1788 (Rex & Cormick 204: 27-8). The first physical encounter between the Djiringanj and European people traveling through their land came ten years after, when survivors of the shipwrecked Sydney Cove walked up the length of the southeast coast on an epic journey of survival. They reported being treated kindly by people in this region (Rex & Cormick 2024: 43). Interestingly, part of the coastal path they followed as they passed though Bunga — a path long used by the Djiringanj and other First Nations people — is still quite evident today.

Europeans started to occupy land in far southeastern NSW in the 1820s and the impact of this was being felt by the Djiringanj people long before the Europeans actually arrived in Bunga in the 1870s. There’s much more to be explored about the patterns of existence of the Djiringanj in this little area before Europeans arrived, the interactions of the two groups and how they both interacted with the environment. This post is a small first step in that direction, by sketching the rough outlines of human settlement at Bunga. The research takes time, but I’m very much looking forward to digging further into all of this. As always, comments are very welcome!

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Colin Cheers, Joss Davies and Mark Spittle for helpful conversations on this subject.

References

Cruse,B, L. Stewart & S. Norman 2005. Mutton Fish: The Surviving Culture of Aboriginal People and Abalone on the south Coast of New South Wales, Aboriginal Studies Centre, Canberra.

Lampert R.J. & P. J. Hughes. 1974. “Sea Level Change and Aboriginal Cosstal Adaptations in Southern New South Wales”, Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 9: 3 (Oct) pp. 226-235

Mulvaney, J. & J. Kamminga, 1999. Prehistory of Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Rex, D. & C. Cormick. 2024. Warra Wai: How Indigenous Australians Discovered Captain Cook and What They Tell About The Coming Of The Ghost People, Scribner, Cameray

Salles T., R. Joannes-Boyau, I. Moffat, L Husson & M. Lorcery. 2024. “Physiography, Foraging Mobility, and the First Peopling of Sahul”, Nature Communications, 15:3430

Leave a comment